Philosophy 363

Ordinary (and Extraordinary) Objects

Philosophy 363: Topics in Metaphysics & Epistemology

Spring 2020

David Sanson

Illinois State University

Tue Thu 8-9:15 am1

Stevenson 227A

Do ordinary objects—tables, trees, dogs, cities, clouds, cars, socks, toes, herds, statues, mountains, rivers, phones—exist? We will consider some reasons for thinking that they do not. We will consider some reasons for thinking that, if they do, they are no more real than a whole host of extraordinary objects. And we will consider some reasons for thinking that ordinary objects exist, but extraordinary objects do not.

Some ordinary objects—toes and tails, for example—are parts of other objects. When do some objects, taken together, compose a further object? We will consider reasons for saying that they always do, and some reasons for saying that they never do, and some attempts to explain why and when they do sometimes, but not always.

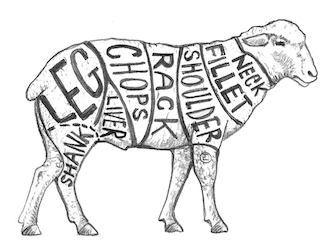

Some ordinary objects—tables and cats, for example—have parts. What parts do they have? We will consider some reasons for thinking that, for every way you could imagine dividing an object, it has parts that correspond to that division. And we will consider some reasons for thinking that objects never have any parts. And we will look at some attempts to say that objects have some parts, but do not have parts that correspond to every possible way they could be divided.

Many ordinary objects—like clouds—seem to have fuzzy or vague or indeterminate boundaries: a cloud is a collection of water droplets suspended in the air, but which water droplets, exactly? Some philosophers think that, upon reflection, we should say that there are lots of overlapping precise collections of water droplets suspended in the air, but none of them are clouds, because clouds lack precise boundaries, and so there are no clouds. Others think that we should say that each precise collection of water droplets is a cloud, so that, for each apparent cloud in the sky, there are actually lots and lots of overlapping clouds in the sky. Is there a way to save our ordinary ways of thinking about and counting clouds, or are we forced to admit that our ordinary ways of thinking fail to align with reality?

Some ordinary objects are natural and some are artifacts. What is the difference? We will consider some reasons to think that artifacts depend on us in distinctive ways, and we will consider some reasons to think we depend on them in distinctive ways. We will also look at some reasons to reject this distinction.

Some ordinary objects are artworks. What makes something an artwork? We will look at some views on the ontology of artworks, and compare them to views about the ontology of artifacts.

Many of these puzzles suggest a worry about the relationship between our concepts and reality. Our concepts divide reality up in specific ways—into tables, trees, dogs, clouds—and not others. The distinction between ordinary objects and extraordinary objects is just the distinction between those objects recognized by our conceptual scheme and those not. But do we have any reason to think that this distinction tells us anything about reality, and not just something about our biases? We will consider positive and negative responses to this question.

Readings will be drawn from contemporary analytic metaphysics, though we will also have occasion to read bits and pieces from Aristotle, Kant, Marx, Nietzsche, and Heidegger, among others.

For a more details about some of the puzzles we will consider, see the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on “Ordinary Objects”.